From polyjargon to programs: Systems thinking in assessment

Diana Saragi Turnip and Priya Khanna Pathak, University of New South Wales

At the recent Australasian Symposium on Programmatic Approaches to Assessment (ASPAA), held on 19 September 2025 with over 480 participants registered from across the sector, we heard how systems thinking is starting to untangle the mess of fragmented assessment practices and approaches. The conversation reinforced that program-level and programmatic approaches to assessment are not just buzzwords. They are emerging necessities for sustainable education and a future-ready workforce.

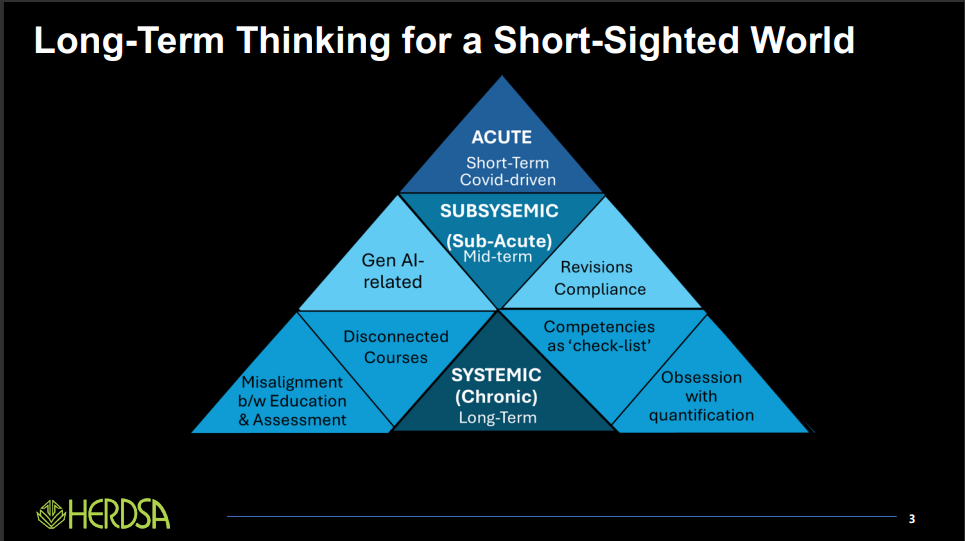

It has been widely observed that higher education often responds to disruption with short-term fixes, and that the impact of such events merely exposes long-standing systemic issues rather than creates them. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted rapid, acute changes to learning, teaching and assessment, and the rise of generative AI has triggered another wave of mid-term responses such as new policies, compliance tweaks, and assessment redesigns. As Lodge, Howard, Bearman, Dawson and colleagues (2023) argue in Assessment Reform for the Age of Artificial Intelligence, these disruptions have simply resurfaced challenges that Boud and Associates (2010) had already identified in Assessment 2020: fragmented curricula, misalignment between assessment and learning, and an overreliance on measurement rather than meaningful capability.

As the pyramid below shows, long-term problems need long-term solutions. What is needed now is a systemic, whole-of-program approach to curriculum and assessment that addresses root causes rather than symptoms.

Programmatic and program-level approaches to systemic assessment reform

In recent years, programmatic and program-level approaches to assessment redesigns have been discussed significantly, at both the university and discipline levels. Programmatic Assessment, which originated in medical education, is a major pedagogical and socio-cultural shift from reliance on single high-stakes assessment events towards longitudinal and meaningful multi-data-point collation across a well-defined competency or capability framework. The underlying assumption is that students do not need to “prove” competence in one exam, as competence, by its very nature, cannot be ascertained by a single observation. Instead, evidence, based on a sufficient sample of observations around the construct to be assessed, needs to be gathered across authentic tasks, portfolios, and feedback conversations, creating a more holistic system that connects assessment with learning rather than separating the two.

Two key benefits stand out when the assessment is designed this way. First, the most immediate one is that it lowers undesirable stress for students, who no longer face the cliff-edge of one-shot exams. Second, it builds trust between learners and educators by turning assessment into an ongoing conversation, with diagnosis and growth taking priority over grading. A word of caution however: if the data are not collated meaningfully across competencies or well-defined capabilities, then every assessment will be perceived as ‘high stakes’ by the students; hence, the underlying educational design in programmatic assessment needs utmost attention.

Running parallel, program-level assessment ensures that assessment tasks are aligned vertically across years and horizontally across courses, with program-level outcomes or capabilities serving as the overarching framework. Both programmatic and program-level reforms to assessment, therefore, cannot exist without a longitudinally designed curriculum.

That is why assessment design must be a team sport, although the game of education is an infinite one. Programs, not just individuals, need to coordinate sequencing, workload, constructive alignment, and policies. When done well, program-level assessment makes visible how tasks connect to broader learning outcomes and career readiness. This includes embedding graduate capabilities like information-seeking, the ability to identify needs, evaluate sources and apply knowledge in complex, unfamiliar contexts, which is essential for workplace adaptation and lifelong learning.

How can we achieve a holistic assessment design

Here is where systems thinking comes in. Programmatic and program-level approaches are complementary layers of the same system: one provides evidence across time to make holistic judgements about competence; the other ensures those data points are distributed and aligned with graduate outcomes. Together, they form an ecosystem of learning that gives students coherence, progression, and purpose.

What is getting in the way?

Of course, there are barriers. The ASPAA discussions surfaced several recurring challenges:

Inadequate understanding of the nature (ontology) of competence and capability, leading to attempts to solve the problem of assessment without paying adequate attention to other elements of curriculum.

Stakeholder buy-in remains a challenge. Without staff and students committed to the shift, reforms remain policy on paper.

Privileging resources such as technology over pedagogy. Programmatic and program-level approaches demand rethinking how we can optimally use technology, data, and staff time, while keeping good pedagogical design at the core.

Language overload continues to cloud the conversation. With too many competing terms, the central message of what we are trying to achieve with assessment reform that addresses our long-term problems gets lost.

AI presents both promise and problems. While it can support personalised feedback and richer portfolios, it also raises questions of integrity and adds another layer of complexity.

The initial hype around generative AI has abated, but the challenge is far from over. What is needed now are coordinated, programmatic responses that move beyond patchwork fixes and proctoring. This means re-examining what should be assessed and how, embedding ethical and collaborative use of AI, and designing assessments that privilege thinking, decision-making and judgement, qualities that AI cannot replicate.

Why this is needed now

As we argued previously, higher education cannot afford fragmented responses to AI. What is needed is a unified, systems-thinking approach that cuts across silos and ensures program-wide coherence.

The urgency is clear. Employers increasingly seek graduates who can adapt, think systemically, and integrate knowledge across disciplines to address complex challenges. The OECD Learning Framework 2030 emphasises that future-ready learners must develop transformative competencies such as creativity, adaptability, responsibility, and systems thinking to navigate uncertainty, collaborate effectively, and contribute to sustainable, inclusive societies.

For systemic redesign to succeed, certain enablers are essential: shared principles, a clear vision, committed teams, and genuine dialogue. Leadership must back the change; resources should prioritise people over processes, and scholarship should be celebrated. Above all, reform should focus on one coordinated change at a time, ensuring programs move forward with coherence rather than scattershot fixes.

Reforming assessment is not limited to improving individual tasks or processes. It requires transforming the wider learning ecosystem so that assessment, curriculum, and pedagogy work together to support meaningful learning. The goal is not only to assure learning through assessment pathways, but to design educational experiences that also assure learning for students by strengthening engagement, feedback and growth.

Patchwork fixes will not cut it. What higher education needs now is a bold, systemic redesign. Universities cannot keep refining the “candle” of lectures, long semesters and high-stakes exams. Like the shift from candlelight to the light bulb, the task is to rethink the whole system so that learning is more focused, active, inclusive, and aligned with how students live today.

As ASPAA reminded us, these are not just conceptual shifts. They are urgent, sector-wide priorities that will define whether we can turn candles into lightbulbs.

In short: all we need is to change the way we think.

Diana Saragi Turnip, Educational Developer Nexus Program, Medicine & Health, University of New South Wales

Priya Khanna Pathak, Nexus Fellow, Medicine & Health, University of New South Wales