Encouraging ‘soft skills’ in creative arts

Deborah Tillman, UNSW

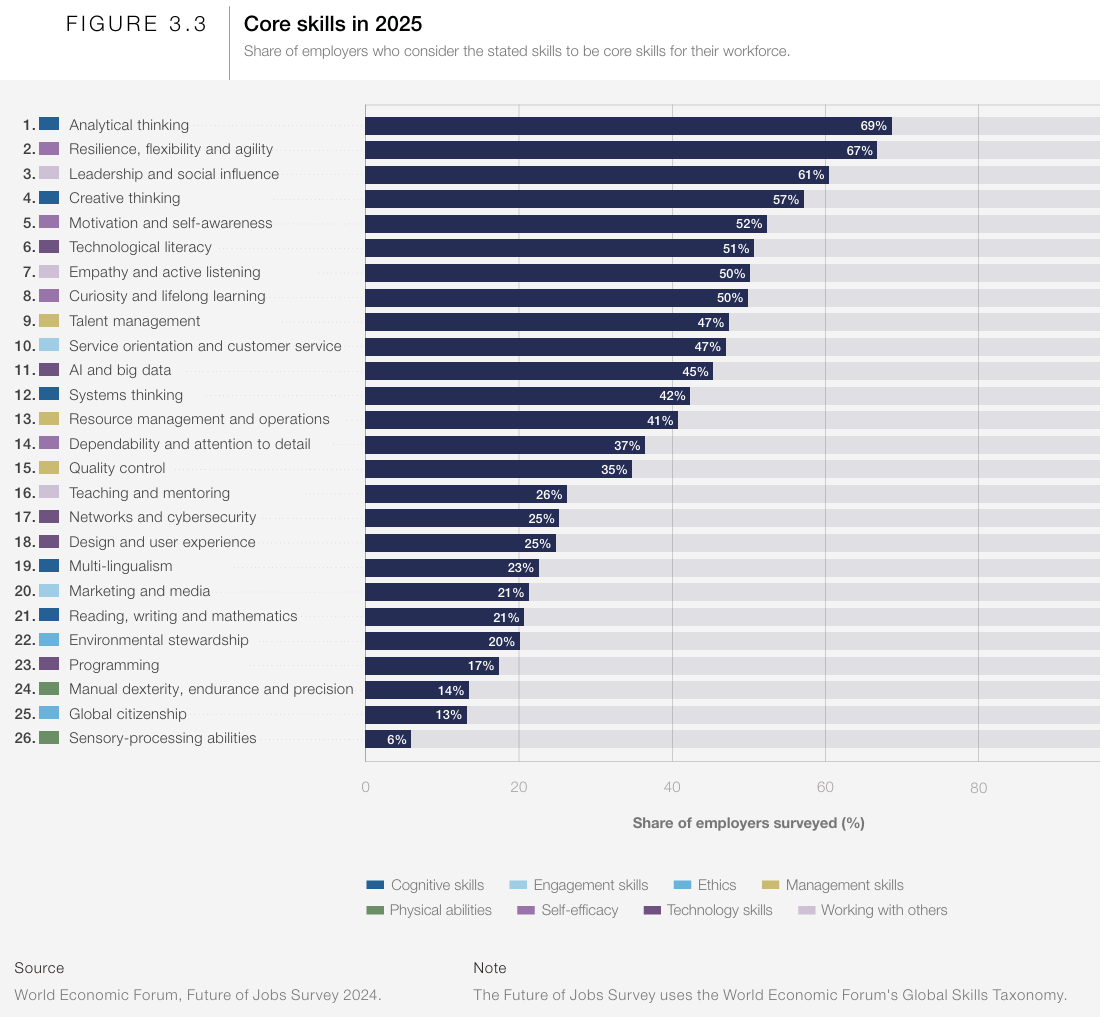

Part of practice-based, research-informed teaching within an Art & Design school is keeping a close eye on your graduates. With leadership and creative thinking in the Top 5 Core Skills sought after ‘soft skills’ in 2025 for Creative Industries, and with curatorial leadership being highly relational, I would like to share a recent experience in pivoting from a set teaching plan to the extension of a studio art practice into public space.

I convene courses and lecture/tutor into the Master in Curating and Curatorial Leadership (MCCL) at UNSW’s School of Art & Design and am Director of Lifelong Learning for the Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture (ADA). This situates me at the nexus of graduation, upskilling, internships and employment. As such, I keep a close eye on my graduates. One particularly gifted former student was set to curate an independent group exhibition at Bankstown Art Centre (BAC) in October/November 2026. However, due to the pressures of independent curating necessitating multiple roles, they were unable to curate due to competing contracts. As we know each other well, the Director of the Art Centre, Rachael Kiang, invited me to step in as co-curator. In recommending and scaffolding a pivot plan, we were able to set up a sophisticated student exhibition quite quickly, answering the call to industry for our specific UNSW skillsets and non-traditional ways of teaching.

Core Skills for Graduates

At a recent Skills Showcase for higher degree education through UNSW’s School of Education, Deputy Dean Professor Stephen Doherty shared the below statistics regarding core skills sought after in our graduates:

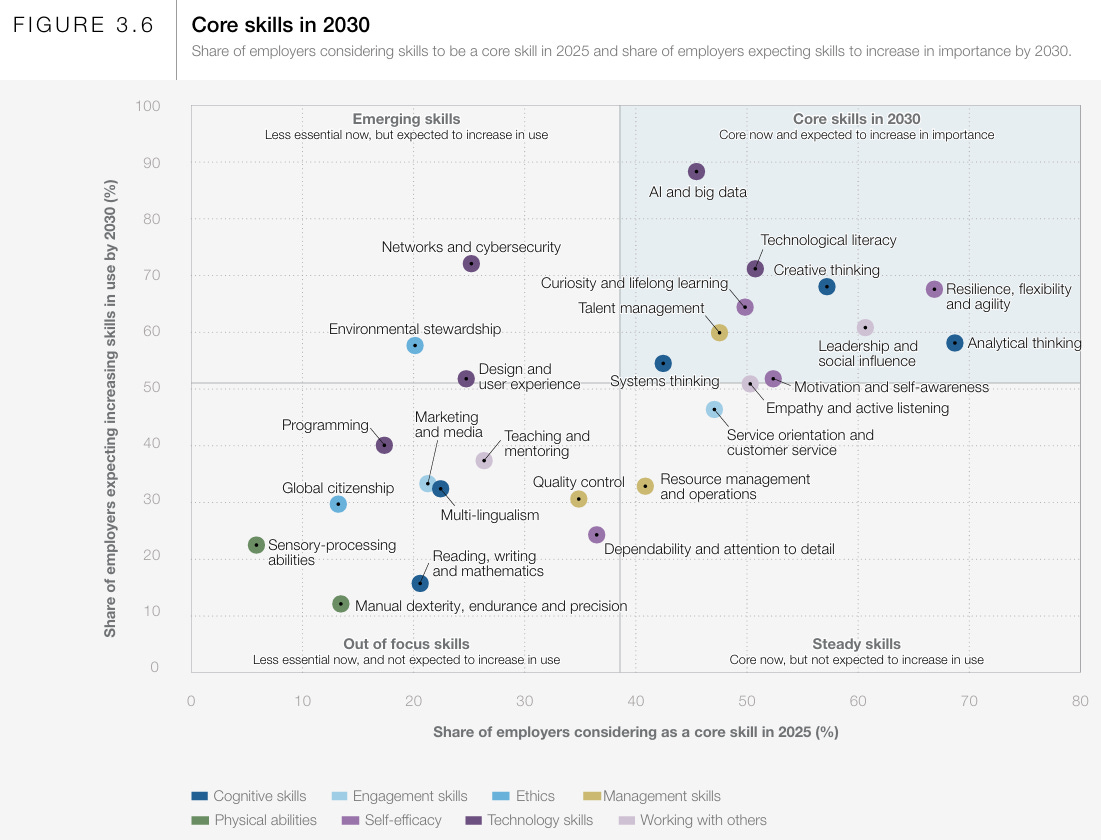

This was followed by a scatter graph separated by quadrant analysis. The section highlighted reports the sought after core skills leading up to 2030. Again, creative thinking and leadership feature.

I share this analysis because it is relevant to our work in extending the studio through the MCCL. Within the pivot plan, we were able to offer the development of exactly these skillsets. Regarding the content of the curatorial enquiry aligned with our industry partnership with BAC, we were also able to test the other skills listed in that quadrant, thus futuring and experimenting with skillsets around:

AI and big data: an understanding and use of AI and the impact of big data will become so necessary, that AI won’t be keeping graduates from employment, rather people skilled in using AI will take the top spots.

Technological literacy: the use of multiple platforms from photography to the manipulation of code was demonstrated in the exhibition by university students and alumni. This ease of digital engagement with technology needs to be experienced in situ for creative practitioners, and the results fed back to the university for teaching the next generation.

Curiosity and lifelong learning: the engagement of a general public audience was sought after by the artists, and BAC itself offers creative courses in the arts including exhibition, dance, school workshops and residencies. This is an ideal industry relationship in the creative sector.

Talent management (curator/artist): we are always seeking real life engagement with industry within the university; this exhibition allowed artists and curators to practice and learn at the same time in a collaborative and immersive way.

Analytical thinking: it’s very natural for creative people to learn as they go, especially in regards to technology. For the current PhD students participating as artists, they were able to take note, record, analyse and use the information about their artwork (and by extension, their practice) to qualify themselves further via qualitative data for their PhD submission.

This case study offers a true introduction to exhibition culture in the arts scene, one of moving quickly and relying on relationships to achieve set goals.

Creative coding

The curatorial rationale for the exhibition was around the human element of creative coding. Titled Care in the Code, we invited emerging artists (Chloe MacFadden, Zoe Li and Wendy Yu) to utilise the gallery floor as an extended studio. When asked in the closing artist curator panel why the gallery was useful in this way, all of them commented that engagement with a diverse audience different to their university colleagues or creative peers was integral to progressing their work. Though it doesn’t happen in the classroom, observing the general public engaging with their works is essential to their iterative process of practice-based research or reflective practice, and takes it from a world of uncertainty into a world of curiosity and growth as a creative practitioner. It closes the loop of creating a live, time-based, performative artwork; at least for that moment in time.

As these skills are becoming so essential, perhaps we should cease calling them soft, and value them as necessary. In the creative arts, there are worlds of hidden labour, and dealing with people – the general public, potential investors or gallerists – all come with the requirement that you can people manage; even if it’s just yourself. This case study shows that students can work together with their mentors in a live environment, mimicking all of the skills required, not just higher degree research skills.

To view the full artist panel moderated by curators Rachael Kiang and Dr. Deborah Tillman, please visit filmmaker Liam Black’s Vimeo channel.

Dr Deborah Tillman, Director of Lifelong Learning, Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, UNSW